(extracted from "SPIRITUAL SEX: Secrets of Tantra from the Ice Age to the New Millennium," by Nik Douglas, © copyright 1996. All rights reserved)

The majority of India's indigenous tribal people are Dravidian, a linguistic group that includes Tamil, Telegu, Khond and Oraon languages. They are of "Australoid" racial stock, related to the aborigines of Australia who first migrated there from India at least 60,000 years ago. The territory controlled by Dravidian tribes once extended from Southern Iran to Australia. Originally, in the distant archaic past, these people must have migrated out of Africa.

As in Africa, the culture of ancient India was largely matriarchal. Its people celebrated the spiritual mysteries of birth, the seasons and lunar cycles, renewal, rebirth and transcendence. The diverse dark-skinned Indian aboriginal tribes worshipped spiritual powers associated with fertility, virility and the after-life. They have done so since the dawn of history.

For thousands of years, India's tribal people used anthropomorphic images or "idols" in their spiritual rites. They used selected herbs, flowers and trees in their rituals and plant-drugs to help induce trance states. Worship was accompanied by mystic phrases, diagrams and gestures, and by sexual acts. Like most tribal people world-wide, they believed in the efficacy of spells, charms and amulets.

THE ANCIENT INDUS VALLEY OR "HARAPPAN" CULTURE

The remains of the ancient Indus Valley culture were "discovered" in the 1920s, following some initial finds towards the end of the 19th century. The brick built city of Harappa, located near the Ravi river in Punjab, Pakistan, was the first site to attract attention, followed by Mohenjodaro and Chanhudaro, further South on the river Indus. The close resemblance between objects from the Indus Valley sites and those from ancient Sumeria, in Southern Iraq, dateable between the third and fourth millennium B.C.E was soon apparent.

Initially the term "Indo-Sumerian" was used to describe antiquities from the same period in the Indus Valley and Southern Iraq. Since the 1920s numerous other Indus Valley or "Harappan culture" sites have come to light, covering an area of more than 1.3 million square kilometers, larger than any other archaic civilization. Very recently, as a result of analysis of landsat imagery and studies in earth sciences, it has been shown that a now-dried-up greater river system, referred to as the Saraswati, was integrated with the Indus river system in the same period, with numerous archaic settlements scattered along it.

People of the Harrapan culture, which was well established by the end of the fourth millennium B.C.E. , were expert potters and worked with steatite, ivory and other exotic materials. They used copper, gold, and semi-precious stones and had large ships which they used for trade. Their religion was essentially pagan, "animistic", and included tree and animal worship as well as the use of sexual symbols such as the penis and vulva.

Harappans used a pictographic language comprising about 370 separate glyphs of which about 135 are frequently occurring basic signs. Their pictographs were read from right to left and had syllabic values. The complete absence of any long documents in Harappan writing suggests that these people generally used perishable materials such as bark, palm-leaves, cotton or leather to write on. Unfortunately no-one has yet been able to satisfactorily decipher the short inscriptions which have survived on seals, engraved copper or on pottery.

The city of Mohenjodaro covered at least one square mile and is better preserved than Harappa. Both of these principal cities were well planned, with streets laid out in a regular grid pattern and oriented to the cardinal directions. Street widths and brick sizes were standardized. Most houses were served by a built-in drainage system and had chutes for garbage disposal. The main street at Mohenjodaro was more than half a mile in length and about thirty-three feet wide. Perhaps as many as 40,000 persons lived there and were involved in industry and trade. The most spectacular features of Mohenjodaro are the Great Bath and the Granary. There were no large temples. Small sepulcher shrines, very much like the samadhi shrines of modern Hindu sadhus or Yogis were quite common in Indus Valley culture.

THE MYSTERY OF THE SEALS AND INDIAN TANTRA

Approximately 2500 small but exquisitely made intaglio seals of the ancient Harappan or "Saraswati-Indus" river culture are known. Most were recovered from excavations at the ruined cities of Harappa, Mohenjodaro and Chanhudaro. Others were found at Kalibangan in Rajasthan, the now landlocked ancient port of Lothal, North of Bombay, and elsewhere.

Most seals were carved from blocks of light-colored, fine-grained steatite, and after carving, the surface was coated with a glaze and fired. Harappan seals are carefully composed and reveal great artistry in the manner of treating their subject. About half of the surviving examples depict a male animal shown in a heraldic way, generally with a line or two of pictographic "text". About 2% of the seals depict humans engaged in different kinds of ceremonial activities.

The best known Harappan seal is one identified by archaeologist Sir John Marshall as Shiva Pashupati, the Yogic "Lord of Beasts". This seal is often cited as evidence that people of the Indus Valley culture knew Yoga and practiced Tantra. It is, however, not the only known example of this subject from this culture. There are several others, of which four are particularly significant.

The "Marshall" Shiva seal depicts a buffalo-horned masked male figure seated on a throne in a version of the cross-legged "lotus" posture of Hatha Yoga. The Yogi's penis is erect, with both testicles prominently visible. The precise placement of both heels under the scrotum is an advanced Tantric Yoga technique known as bandha, meaning knot or "lock". It is normally used to sublimate and redirect sexual energy and can endow the practitioner with spiritual powers.

On the Marshall seal the Yogi sits on a type of throne or bed which is supported by an object resembling the hour-glass shaped double drum (known in Hindu ritual as the damaru) normally associated with Shiva and with shamanistic rituals throughout Asia. The top and bottom of this drum takes the shape of horns, tying-in to the horned headdress.

The Yogi's hands are both shown placed on the knees, in a typical meditational gesture which aids energy circulation. His chest is covered by a five-tiered "V" pattern formed by ten stripes. Both arms are divided into stripes, as if intended as a notational device; four small stripes are followed by a fifth larger one and then the sequence repeats. A total of thirty distinct stripes are drawn on the body of the Yogi; ten on each arm and ten over the chest. Some type of calendrical lunar-oriented notation seems to be represented here, indicating days in a month. Many Harappan seals have notched markings on horns, branches, arms or on the bodies of animals, reminiscent of Paleolithic-period notational marks commemorating calendrical data.

Shiva's horned headdress is also divided into stripes; twelve on each horn, plus eight evolving into a sort of crown, echoing the "V" pattern over the chest, for a total of 32 stripes. A possible 33rd stripe can be seen at the central uppermost part of the crown. Immediately above this is a pictograph, also horn-like with two stripes at each side and a central divided circle.

A large tiger rears upwards by the Yogi's right side, facing him. This is the largest animal on the seal, shown as if intimately connected to the Yogi; the stripes on the tiger's body, also in groups of five, emphasize the connection.

Three other smaller animals are depicted on the "Marshall" Shiva seal. It is most likely that all the animals on this seal are totemic or "heraldic" symbols, indicating "tribes", "people" or geographic areas. The heroes of the Mahabharata, the Hindu epic, had animal symbols on their battle standards. The ancient Egyptians and Sumerians both used animal symbols to distinguish people from different areas. Known as neters or "cosmic visions" in Egyptian culture, these totemic symbols remained unchanged throughout the entire historical period. Many indigenous tribal people of India still have animal totems which signify their different "families" and the geographical zones to which they are connected. On the Shiva seal, the tiger, being the largest, represents the Yogi's people, and most likely symbolizes the Himalayan region. The elephant probably represents central and Eastern India, the bull or buffalo South India and the rhinoceros the regions West of the Indus river.

Immediately beneath the throne, as if decorating it, are two mountain goats (one mostly missing, due to the break, but enough has survived to restore the complete composition). These goats are symmetrically placed, mirroring each other. They are separate from and smaller than the other animals shown and are "vehicles" or "magical allies" of the seated Yogi; emblems of his authority or origin "in the wild mountains" of the North.

This Shiva seal is a carefully contrived glyph loaded with meaning. It would, of course, be helpful to be able to read the single line of pictographs. Understanding an unknown pictographic-derived script in an unknown language is extremely difficult. But until there is certainty about the language spoken by the inhabitants of the Indus Valley region, and the evolution of their script, we must focus on the precise iconographic or "heraldic" information easily accessible to us.

Pictographs or ideograms are supposed to be understood by reading the parts which make up their whole, and by the overall "composition" and impact. The saying that a "picture is worth a thousand words" is particularly true for the intricate and carefully designed Harappan seals, which reveal most of their secrets without the necessity of reading the brief inscriptions.

THE MOHENJODARO DANCING GIRLS

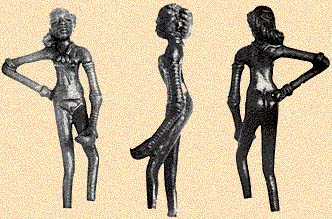

The best known artifact from the Indus Valley culture is an approximately four inch high copper figure of a dancing girl. Found in Mohenjodaro, close to a fireplace in one of the rooms of a large structure, this exquisite casting depicts a dark skinned young tribal girl of "aboriginal" type. She is almost naked and her long hair is tied in a bun. Bangles entirely cover her left arm, a bracelet and an amulet or bangle on her upper right arm, and a cowry shell necklace is around her neck. She is posed in a dance posture, her right hand on her hip, her left hand clasped in a traditional Indian dance gesture signifying a lotus bud, symbol of spirituality. Though small, this archaic metal sculpture conveys a lot of information.

The best known artifact from the Indus Valley culture is an approximately four inch high copper figure of a dancing girl. Found in Mohenjodaro, close to a fireplace in one of the rooms of a large structure, this exquisite casting depicts a dark skinned young tribal girl of "aboriginal" type. She is almost naked and her long hair is tied in a bun. Bangles entirely cover her left arm, a bracelet and an amulet or bangle on her upper right arm, and a cowry shell necklace is around her neck. She is posed in a dance posture, her right hand on her hip, her left hand clasped in a traditional Indian dance gesture signifying a lotus bud, symbol of spirituality. Though small, this archaic metal sculpture conveys a lot of information.

Several eminent scholars have taken this casting to represent a temple dancer or sacred harlot, perhaps because of her nakedness, the "come hither" dance-posture, with hand on hip, and the expression of self-assurance on her face. Whatever the sculptor intended her to portray, this small figure confirms that the Harappan people were neither shy of nakedness nor of explicit sensuality. A second metal casting of a dancing girl was also found at Mohenjodaro, but is rarely reproduced in books. Slightly larger than the better known example, it is unfortunately not in such fine condition. The pose is similar, but reversed.

Both these metal castings clearly depict a nubile young woman in the role of sacred dancer and effectively convey feelings of sensuality and spirituality. These two ancient figurines of sacred dancers may be the earliest known representations of dakinis, images of female initiatory power, of paramount importance in Tantric tradition. Together with the several Shiva seals from the same archaic culture, they confirm beyond any doubt that the archaic pre-Vedic Indians had Tantric Adepts among them.

AN ARCHAIC TANTRA MATRIARCH FIGURE

|

A large and unique wood-sculpture of a squatting female is one of several enigmatic tribal-style sculptures from greater India, some of which, attributed to the Mehrgarh (7,000 to 5500 B.C.E) and Indus Valley (circa 3300-1300 BCE) cultures, shed light on an early Tantric matriarchy.

Realistically carved, she squats in birthing position lifting her dress to reveal her vagina, stained from offerings. A shawl covers her left shoulder, her right breast bare, hair pulled back and tied in a style favored today by tribeswomen of eastern India. She wears ear-rings and the upper part of her right arm is tied with an amulet of type found on several Harappan sculptures. Her mouth has tattoos around it, a custom of several archaic cultures and signifying that she represents a matriarch, a married woman who has borne children. Some cultures where mouth-tattooing survives are among Ainu women of Japan; Paiwan tribal women of Taiwan; the Kondhs of Orissa, India; as well as Maori women of New Zealand. This extraordinary sculpture was likely passed down through a matriarchal tribe. Originally attributed to the historic Shunga period, circa 300 B.C.E., but following a wood test was re-attributed to circa 2400 B.C.E. A more recent radiocarbon test (2012) suggests a more accurate date is the seventeenth century A.C.E. More science may need to be applied to unravel the correct dating, which still leaves us with mysteries of iconography and context. |